New Zealand 2025 Energy Stock Take

Taking stock of our energy system as we enter 2025 and projections for the year ahead.

Last year was tough for NZ Inc. We had two successive quarters, June & September 2024, with economic contraction. The September quarter being significant at -1.1%.

I expect the December quarter results to be worse and the annualized figure to also be negative. New Zealand’s economy in summary is contracting.

This comes as little surprise given the energy system is also contracting. Specifically, as demonstrated by the energy shortages experienced over the past winter.

The economy is simply energy transformed.

Although it may not have been apparent to most New Zealanders going about their daily lives, there were significant curtailments of economic activity by big industrial energy users in August last year.

The gas and electricity supply for these heavy industries were redirected to the electrical grid to keep the lights on for smaller businesses and New Zealanders in general.

Methanex (methanol producer) and Tiwai (aluminium smelter), both major exporters and contributors to NZ’s GDP, took the full brunt of this “demand management” by reducing their production and on-selling their contracted energy to fill shortages in the general electricity generation market.

In short, they stopped exporting so we could keep our lights and toasters on at home.

Methanex in particular is being severly hampered by energy constraints, specifically the domestic natural gas shortage. In 2023 they reported a total production of 1,380,000 tonnes of methanol in 2024 this has dropped by more than 50% to 670,000 tonnes.

The Tiwai aluminum smelter reduced production by an estimated ~35% in the past winter to re-direct electricity to the grid. This reduction in output has a long tail effect on the economy. Tiwai reduced production in August and is not anticipated to be at full production until April (9 months of reduced economic output).

For the first time residential electricity demand is exceeding industrial demand. This is a clear signal of deindustrialisation.

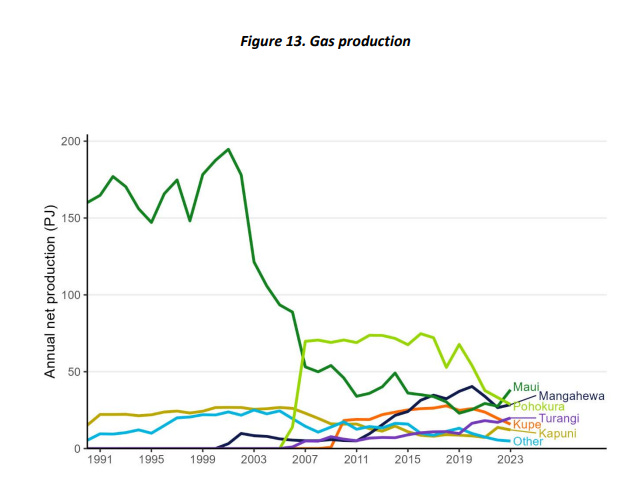

In fact, we can see that New Zealand had a deindustrialisation inflection point in the early to mid 2000’s when viewing the charts below.

Domestic industrial electricity use peaked around 2005 and domestic industrial natural gas use peaked around 2003.

NZ has never exported electricity or natural gas so both of these energy streams have been used entirely for domestic industrial activity.

This large-scale reduction in the production of goods and services will undoubtedly worsen the current recessionary trajectory as we head into 2025.

BNZ said this month that New Zealand's manufacturing sector "remained in contraction over December"

In its latest BNZ - Business NZ Performance of Manufacturing Index, the seasonally adjusted PMI (Performance of Manufacturing Index) was 45.9 - with a reading below 50 indicating that manufacturing is declining.

"Although this was up from 45.2 in November, it was still well below the average of 52.5 since the survey began. The sector has now been in contraction for 22 consecutive months," BNZ senior economist Doug Steel says.

Monetary policy will not turn things around.

When the December 2024 quarter figures are released, the regular stream of media friendly, celebrity economists will offer their opinions in the NZ Herald and on the Mike Hosking show. The common narrative will be “there’s a monetary fix to this”.

If these economists even recognize that there is an energy component to the economic situation, they will undoubtedly make the error of putting money and energy in the wrong order.

Energy comes first.

Monetary policy can’t fix this problem, but it can definitely make it worse. Any form of quantitative easing (printing money) will only be inflationary if we do not have the energy to transform into goods and services.

In a nutshell New Zealand’s economy is energetically constrained.

This is different to any other recent recession. In the past economic activity could be stimulated by monetary policy because we were not energy constrained.

This time the economy needs energy, not monetary stimulus to grow.

It’s important to recognise when solutions of the past will not fix the current paradigm. This time around the fundamentals are different. I’ve yet to meet a NZ economist who has recognised this and therefore they make the error of using past solutions applied to current context.

Energy Outlook

So, that said, let’s take a look at the energy situation heading into 2025 and if we can see any respite from our current economic woes.

Natural Gas Supply

This is a pretty grim picture we have less than half the daily production that we had in 2020 and the rate of decline is steep.

For context, New Zealand uses its domestic natural gas for the follow key industries as both an energy source and / or raw material:

Petrochemical production (Methanol).

Fertiliser production (Urea)

Electricity production (Huntly gas fired units & various peaker plants)

Dairy industry (Fonterra’s North Island boilers).

Foresty (timber product drying kilns).

Food manufacturing (primarily in South Auckland).

The natural gas production trends in the chart above clearly explain the following winder economic trends:

Reduced petrochemical export earnings.

Increased reliance on imported energy, namely coal to fire at Huntly power station.

Increased reliance on imported agricultural fertiliser.

It is also the real reason Fonterra are electrifying their boilers in the North Island, natural gas security of supply concerns (more on that in another post to come).

It is why we are discussing importing LNG (liquified natural gas).

It is also why dry year hydro lake levels are felt so acutely, like they were last winter, when there is not enough gas to run the Huntly gas units and various gas fired peaker plants at full capacity.

I do not see any fundamental improvements in the natural gas supply over the coming year. The drilling that is currently in progress, which is minimal, is in field development (small increased recovery from an existing field) and not a large-scale new development that would be required to significantly lift the current natural gas supply constraints.

Furthermore, drilling has a long lead time and is expensive, even in an existing field due in large part to NZ’s regulatory regime. The wheels of bureaucracy turn slowly and need lots of money to lubricate them.

Generally speaking, anyone with money or patience to develop a new field in NZ has packed up and left. The previous government has created a situation where New Zealand’s approach to drilling is uncertain from one election to the next, and we now present too much sovereign risk (government generated risk), so they take their money elsewhere.

Coal Supply

Coal is an important component of the NZ electricity supply in the absence of natural gas.

New Zealand typically uses hydro for baseload electricity generation, with wind and solar being added in intermittently.

This system requires something called firming capacity (something that you can turn on and off to fill the gaps of renewables and rainfall). Natural gas was the primary firming energy source since about 1982. In the absence of natural gas we become increasingly dependent on coal for this firming capacity, hence the increased use of coal at the Huntly power station.

Genesis Energy, the operator of Huntly, had a stock of 573,000 tonnes of coal at the start 2025 which is 158,000 tonnes less than the same time last year, according to analysts at Forsyth Barr.

I don’t see this as too much of a problem. Despite a very buoyant global coal market I anticipate that sourcing additional stock if required would be relatively straight forward.

The coal is available, however, there is a limit to furnace capacity, as by direct association the amount of electricity that can be generated from coal at Huntly. as it has always been the intention to replace coal with natural gas and the investment in coal fired infrastructure limited to maintenance only.

Hydro Lake Levels

As described above NZ’s electricity system is particularly sensitive to the hydro lake levels.

We saw this vulnerability play out last winter. Huntly was at full capacity burning coal, and Methanex shut down to redirect their gas to peaker plants (fast dispatch gas turbines for firming) which were also at full capacity.

The electricity market spot prices skyrocketed, and emergency provisions were enacted to allow the hydro lakes to be drawn down lower than what the resource consents allowed for.

As of last week, hydro lake levels are only slightly below average for this time of year.

However, spring and summer inflows to the lakes rely in large part on the snow storage volumes that have accumulated over winter. In the past year the volumes stored over winter were much lower than average. This means that the lake levels heading into the coming winter will be entirely contingent on the volume of rain the catchments recieve between now and late September.

Generation Capacity

New Zealand companies love to promote how green they are. As a result we see lots of press releases about renewable energy projects. So theoretically we should have extra generation capacity with all these renewables coming online that are not dependent on gas, coal or rain, so let’s take a look.

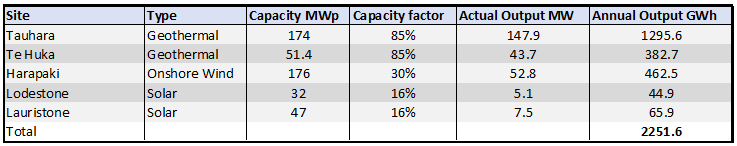

The following table is what has been added or is expected to come online in time for winter. Noting that not everything is captured here. There are a handful of smaller 5-10MW solar projects that are not included. These don’t really have any impact at scale and especially not in winter.

On face value this looks encouraging with the ~2200 GWh of generation capacity added to the system. The bulk of which is high quality baseload geothermal that is not subject to the vagaries of the weather and available on those frosty, calm, and dark winter mornings.

However, at the same time the 300MW TCC gas fired unit at Stratford has been retired. This equates to ~2200 GWh of generation that is coming out of the system.

Essentially, we have zero net change in generation capacity, and a bit less reliability.

The caveat to this is that the TCC unit, although technically retired from service, still has 3000hrs of run life available if needed.

That is of course only if the natural gas needed to run it could be secured, which would likely have to come from Methanex production curtailment. Which essentially means we are now having to make tradeoffs between economic output (quality of life) and keeping our toasters on.

Demand

As a result of NZ’s large-scale deindustrialisation, electricity demand is down 3.2% on the same time last year according to Meridian Energy.

This is of course a double-edged sword. It gives some relief in the event of dry year generation constraints, but as we know negative change in energy used = negative change in GDP.

This again is not a good indicator in terms of the economy returning to positive GDP figures.

Projections for 2025

We largely find ourselves in the same situation as last year, but with an even higher reliance on the weather.

Expect winter energy prices to be very high and black outs are not off the cards if we get below average levels of rain between now and September / October.

Recent high prices in the international dairy auctions may help our overall GDP, but it will only serve to mask a general decline in economic output. Overall trend will be zero growth at best. In the event that we have another dry winter we will see a series of negative GDP figures in 2025 also.

Prime Minister Luxon has ambitions to grow the economy and is on the right track by saying we need a “flood of generation”.

However, his government paradoxically will struggle to see this ambition realised due to the Bradford reforms of the fourth National government in 1998, which saw all the large generators being broken up and privatized.

As competing publicly traded entities they now have fiduciary duty to their shareholders. This makes it very hard for a board to sign off on a “flood of generation” because it would significantly increase supply, thereby reducing the price they can charge and the returns they can return to shareholders. The other reason it’s hard to sign off on any investment in generation is that we now have reduced industrial demand (ironically because the price got too high), so nobody in their right mind would sign up more generation when the customers are closing up shop.

The government is further conflicted here. As the major shareholder in all these entities, they benefit from high electricity prices in the form of dividends. These dividends are desperately needed to prop up crown revenue, which is down as a result of reduced tax take in a recession.

The government is not being transparent with the electorate here. They have the 51% controlling share of Mercury, Meridian and Genesis. The obvious route to a “flood of generation” is to redirect the dividends of all three entities into large scale, high quality, dispatchable, baseload generation. To meet this criterion the investment would have to be in large scale hydro, geothermal or nuclear.

Doing this would require the government to have foresight and see that dividends on power generation is not the sweet deal they think it is, and in fact drives overseas investment away, impoverishes your people, and makes it just generally hard to do business.

A longer-term view would be to forfeit immediate term dividends in favour of a larger tax base, which would result in better return over time.

It is for this reason that I do not predict there being a “flood of generation”.

Offshore wind investors, who’s projects are eye wateringly expensive and risky, will be well aware of the conflicts of interest above and will not develop any projects in New Zealand without significant subsidies and offtake commitments by the Government (a commitment to buy the power generated regardless of the market conditions at the time).

Nuclear is unfortunately a bridge too far for New Zealand’s political class.

Further large-scale hydro is geographically constrained and would be a resource consenting nightmare that would take decades due to the land and rivers affected.

As a result, the “flood of generation” will instead be a slow trickle of small wind and solar projects and maybe the occasional battery. The grid will be increasingly fragmented, weather dependent and rely even more on Huntly coal to keep the lights on (much to the chagrin of green activists). Prices will only continue to rise, and the de-industrialisation of New Zealand is baked in long term.

My advice for 2025:

Work towards being self-sufficient and off grid.

Move investments to economies with an energy surplus, these are the only ones that will grow in the coming year.

Watch out for the energy cannibalism from the AI Tech Bros, who will need more energy than some nation states to fuel their tools, and you better believe no petty consenting or activism will stand in their way. They will take it in any form, coal, nuclear, hydro, geothermal…. they don’t discriminate (future post to follow).

Great article. Of particular interest is the rate of dividend payouts to investment in new generation which has seen capacity rise 6% since 2004, despite population increasing 30%. The New Zealand Official Yearbook for 2004 (available on stats NZ) has this scarcely believable paragraph (hindsight is everything of course):

"Projections suggest that New Zealand will have much slower population growth in the future. The population is currently projected to peak at 4.81 million in 2046.

"Assuming fertility levels remain below replacement level, New Zealand would need a sustained net migration gain of nearly 10,000 a year to reach 5 million. Although annual net migration has exceeded 40,000 in recent years, the external migration balance has also fluctuated widely, with several periods of net migration loss."

This was only 20 years ago, but energy companies (and the government before it sold half of them) needed to recognise it could not rest on its laurels of old plants and had an obligation to invest in new projects, if only to be able to retire old ones

Nobody's talked about energy policy very much in this country, or about using domestic energy resources to power industrial development and wean us off the slow puncture of petroleum imports, since the days of Rob Muldoon. Yet it has come back to bite us with our gasfield depletion, which seems to be about as significant as the winding down of North Sea Oil in the UK, a phenomenon similarly overlooked in contemporary discussions of Britain's present malaise, as if nobody remembers the seventies. Does Energy Policy mind if I use one of the graphs, in particular the gas depletion graph, in a post of my own?